The nation went speechless when 50 schoolgirls from a single school in Satkhira, aged between 14 and 18 years, fell prey to child marriage within a span of one and half years during the covid lockdown. According to Ain O Shalish Kendra, there were 1627 (reported) rapes in 2020 alone.

Is crisis gender-neutral? The short answer is no. Neither Covid nor any crisis is gender-neutral. The multidimensional challenges facing the 21st century – from food security to financial stability and climate change- are all, unfortunately, heavily gendered.

While the fuel price hike has made it difficult to bring food on the table for both the genders alike, existing gender inequalities mean that females in Bangladesh (especially married adolescents) are often expected to sacrifice their food consumption so that male family members can have more. According to a global report prepared by the UN earlier this year, some 36 per cent of women aged 15 to 49 years are suffering from anaemia with severe intergenerational effects.

Most vulnerable areas in the country have experienced higher rates of forced marriages as a coping strategy

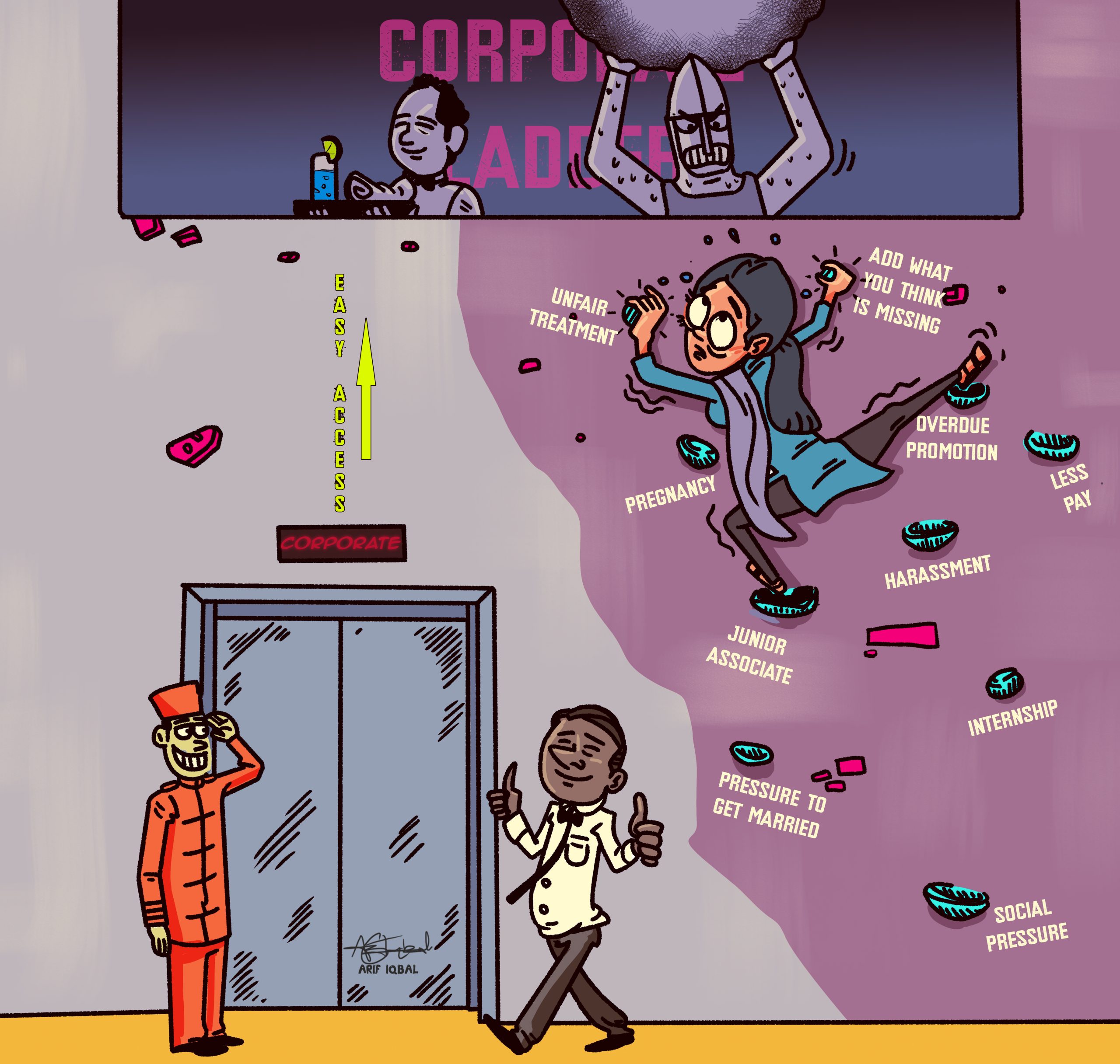

Women are at the frontline for any short-term crisis response putting them at high risk. 95.4% of all female labour work in the informal sector without job security and social protection. The majority of unpaid family labour and care work continue to be taken up by women, irrespective of their formal employment status. They earn, on average, 21% less than men, with only 1 in 4 women having an account with a formal financial institution.

Violence against women continues to remain as a global pandemic without vaccination. In Bangladesh, even with a much-improved policy framework, the incidents of violence remain high, with evidence of hikes whenever there is any crisis. According to UNDP, since the onset of Covid, sexual assault, domestic violence, and dowry-related incidents have picked up mainly in areas with higher poverty levels.

The disproportionate effect of climate change on women and girls is a much-known phenomenon. Most vulnerable areas in the country have experienced higher rates of forced marriages as a coping strategy. The climate crisis, coupled with threatened livelihoods in Cox’s Bazar’s Rohingya camps led to a rise in gender-based violence.

But in Bangladesh, we have even more reasons to worry. With a little more than 50% of our population as women, according to the Bangladesh Population and Housing Census in 2022, we are heading towards two major challenges. First, our demographic dividend ends in four years, meaning we will shift from a highly dense country with a young population to a highly dense country with an elderly population that requires a functioning care economy, traditionally dependent on women. Second, our LDC graduation that is also due by 2026 would mean the end of our duty-free access to RMG exports, loss of our GSP benefit and fall in export competitiveness since the government subsidies will have to be removed post LDC era. 80% of employment in the RMG sector, which has been a major contributor to Bangladesh’s economic miracle, is women.

Employment generation for women is crucial for the struggle ahead. One way to address this is by promoting small, cottage, medium and micro enterprises that absorb 86% of the country’s labour force and contribute to 25% of GDP. But even with policies in place, access to finance remains the strongest hurdle to women’s economic empowerment through this sector. According to the Bangladesh Bank data for 2021, only 4.08% of the CMSME loan portfolio was disbursed to women entrepreneurs against the 10% target. A baseline survey of 8 Upazilas in 2021, found that some Upazila Parishads were only allocating 1% of their annual budgets for women’s development instead of the 3% required. Women’s access to money is structured by gender relations both quantitatively (as in the difference between male and female wages) and qualitatively (paid work that is recognised as productive and unpaid domestic work that is not). Unless explicit thought is given to the design of these institutions, they will tend to instigate new forms of male bias. Women will be excluded from their operations. Even if the policy reforms are not male-biased by design, they will be male-biased by omission.

This bias in gender relations also means that the burden of unpaid reproductive care work falls mainly on women. Traditional macroeconomic policy generally takes the ‘reproductive economy’ for granted, assuming that any disruption, like the ongoing inflation, energy and/or climate crisis in the ‘productive economy’, will be absorbed by and not affect the adequate functionality of the former. An ageing economy in a few years would mean even more time required on domestic duties and care work for women unless more gender-responsive policies are made. The ongoing Time-Use Survey will help policymakers evaluate programs to reduce the unpaid care burden of women. Improving access and affordability of childcare elderly care services, proper implementation of maternity leaves, and promotion of shared and responsible parenthood are some of the ways in which women’s unpaid care burden may be reduced.

Our near-future gendered challenges, if not tackled strategically, will have adverse gendered impacts. All macroeconomic policy needs to include human development targets along with monetary aggregates. The relationship between policy instruments and targets should account for gender differences. For instance, changing indirect consumption taxes affect women more as the manager of household consumption budget compared to direct taxes that affect men more because of their greater access to earnings. Integration of human development targets also allows women to be considered as ends, and not just means. Gender sensitivity into the design of economic policy is not only the smart thing to do, but also the right thing to do.