I: Introduction

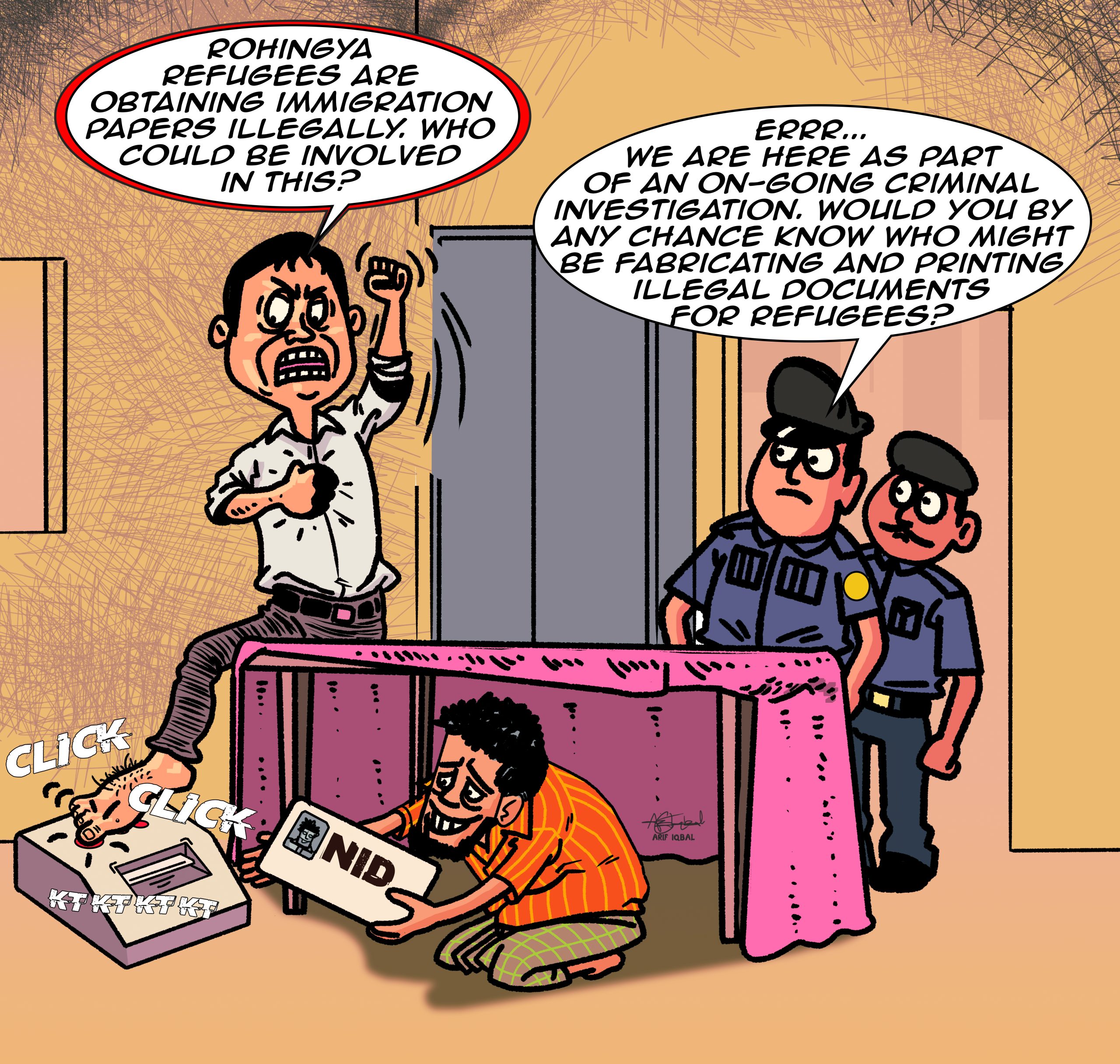

In 2017, the security forces of Myanmar launched an aggressive attack, which included burning entire villages and perpetrating human rights violations, on the Rohingya in the Rakhine State. This led to more than 700,000 Rohingya to flee Myanmar and seek shelter in Bangladesh. Currently, there are more than 900,000 Rohingya in refugee camps at Kutupalong and Nayapara in Cox’s Bazar.

However, Bangladesh’s position is that the Rohingya must be returned to Myanmar, even though their security cannot be guaranteed, especially after the coup d’état in 2021. While the Rohingya have been stateless in Myanmar since 1982 due to a discriminatory citizenship law promulgated by dictator Ne Win, they have not fared any better in Bangladesh, as they remain stateless there as well.

Acquiring citizenship in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s citizenship law is slightly complex. Though section 4 of The Citizenship Act, 1951 grants citizenship to persons born in Bangladesh, it is qualified by section 2 of The Bangladesh Citizenship (Temporary Provisions) Order, 1972 (President’s Order). As in, citizenship is granted jus sanguines, which means that one will receive citizenship in Bangladesh if their parents are citizens of Bangladesh.

In case it is not clear, it is insurmountable to attain citizenship in Bangladesh because if one’s parents are not citizens of Bangladesh, then even if one is born in Bangladesh, he or she does not become a jus soli citizen. This means that the Rohingya that are currently born in Bangladesh are not Bangladeshi citizens.

However, the more important issue, and the one I will address in this paper, is whether the Rohingya, who are refugees in Bangladesh, are entitled to rights and protections that Bangladeshi citizens take for granted.

II: The rights (or the lack thereof) of refugees in Bangladesh

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which is a key legal document, defines a refugee as,

[S]omeone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.

Since the Rohingya are being persecuted by Myanmar because of their religion, they are refugees.

The starting point in Bangladesh guaranteeing the rights of refugees is the Constitution

Article 32 of The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (Constitution of Bangladesh) stipulates,

No person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty save in accordance with law.

There is no comprehensive immigration legislation in Bangladesh that permits a refugee to transition to a citizen

Article 27 of the Constitution of Bangladesh stipulates,

All citizens are equal before law and are entitled to equal protection of law.

Similarly, Article 28 prohibits discrimination and Article 43 prohibits unreasonable searches. However, these rights, along with the right to equal protection of the law, are conferred on citizens of Bangladesh — not to every person.

Strangely, Article 32 prohibits depriving a person of life or personal liberty except in accordance with the law. Therefore, based on a reasonable interpretation, refugees cannot be deprived of life or personal liberty in Bangladesh. Nevertheless, they do not enjoy any of the rights adumbrated above, as they are not citizens of Bangladesh. More specifically, they cannot own property and are not protected against unreasonable searches (more on this later).

The landmark judgment in Canada guaranteeing procedural protections for refugee claimants

The Supreme Court of Canada’s (SCC) landmark decision in Singh v Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) forever changed the course of refugee claimants in Canada. The SCC said that when a refugee claimant’s credibility is at issue, and for refugee claimants, their credibility is usually an issue, they are entitled to an oral hearing under section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter).

To bring this into the context of the Rohingya, if they were claiming refugee protection in Canada, then they would be entitled to an oral hearing only if their credibility was at stake. This means that if their credibility is not an issue, perhaps because there is an abundance of evidence demonstrating that they have been persecuted by the state, then they would not need an oral hearing and would be declared to be refugees by the Refugee Protection Division.

Furthermore, since there is incontrovertible evidence that the Rohingya have been persecuted by Myanmar, they would be declared to be refugees in Canada without an oral hearing.

Once a person has been declared to be a refugee or a person in need of protection, then he or she can apply for permanent residence in Canada, and eventually become a citizen. This way, their life can move forward and the person can establish roots in Canada and becoming a productive member of society.

Who is entitled to Charter protections in Canada and how is it different from Bangladesh?

Aside from certain rights, such as voting and holding public office, everyone inside Canada is entitled to Charter rights. This means that a person who has claimed refugee protection in Canada (keep in mind that this person has not yet been declared a refugee) has the right to the equal protection of law, the right not to be discriminated and the right to be secure against unreasonable searches.

As in, unlike Bangladesh, refugees in Canada enjoy the rights and protections that are guaranteed by the constitution. To further explain, and to use an example, let us assume that a refugee has been charged with murder in Bangladesh. The police would not require a warrant to search the personal property of refugees to uncover evidence, which means they essentially have plenary power, and they can act with impunity.

However, in Canada, if the police, or another arm of the state, want to search the property or the person of a refugee, then they would first require judicial authorization. This means that people who claim refugee protection in Canada are provided with the same procedural and constitutional protections as that of others in Canada, such as students, visitors, permanent residents and citizens.

The patent inconsistency in the Constitution of Bangladesh

Recall from earlier that Article 32 of the Constitution of Bangladesh says that no person can be deprived of life or personal liberty.

To break this down and delineate this further, let us again use the example of murder. If a refugee in Bangladesh is charged with murder, then he or she cannot be deprived of life or personal liberty (e.g., cannot be imprisoned) unless it is done in accordance with the law, which means that there must be a fair trial.

Article 35(3) of the Constitution of Bangladesh further provides that everyone is entitled to a trial “by an independent and impartial Court.” However, and we are finally getting to the heart of the issue, if refugees in Bangladesh are not protected from unreasonable searches and the police conduct a search of a refugee’s property, then that evidence can be submitted to court for his or her purportedly “fair” trial even though the search was not judicially authorized.

To further explain, police searching someone’s property is grossly intrusive, which is why the constitution protects us from it. Moreover, if a search is not authorized by a court, then it is prima facie unreasonable. Therefore, under section 24 of the Charter, a court in Canada can refuse to admit the evidence if its admission would bring the administration of justice into disrepute, such as if the evidence was acquired without a warrant.

Nevertheless, and as I have explained earlier, since refugees in Bangladesh are not protected from unreasonable searches, this means that the police can search the property of refugees without a warrant, and whatever evidence is thereby acquired is not barred from admission into the courts. This is a violation of a refugee’s right to a fair trial, which is purportedly guaranteed to everyone in Bangladesh. Or, in simpler terms, refugees are actually not entitled to a fair trial in Bangladesh even though the Constitution of Bangladesh guarantees it.

Will refugees in Bangladesh fare better if they become citizens?

Yes, but the problem is that, unlike the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act of Canada, there is no comprehensive immigration legislation in Bangladesh that permits a refugee to transition to a citizen. This means that a refugee’s life in Bangladesh will forever be in limbo and the government would have the power to exploit them.

Aside from this grim example, if a refugee is not granted citizenship, then he or she cannot own property in Bangladesh and may even be discriminated against for admission to schools. As in, unlike in Canada, their lives simply cannot move forward and they will never be able to establish themselves in Bangladesh and integrate into society.

Another aspect that Bangladesh should consider

I want to briefly mention that there is one other aspect that Bangladesh should consider, which is that of the religion of the country and the Rohingya.

According to Article 2A of the Constitution of Bangladesh, the state’s religion is Islam. The Rohingya are predominantly Muslim, which is why they were stripped of citizenship in 1982. Therefore, as a Muslim country, if Bangladesh cannot provide a safe haven for the persecuted, who are also Muslims, then who will?

Moreover, since Bangladesh is one of the least developed countries, according to the United Nations, it may not be possible for the country to annually spend $1.22 billion on the Rohingya. Therefore, if nothing else, the economic aspect should be the primary reason that Bangladesh grant citizenship to the Rohingya so that they can gain employment and becoming productive members of society, which will reduce the severe financial burden on the government.

III: Conclusion

While the Rohingya are perhaps not being persecuted by Bangladeshi authorities, they do not have many of the rights that are otherwise provided to Bangladeshi citizens, which means that they will never integrate into Bangladeshi society. Moreover, though they are technically safe in Bangladesh, they can nevertheless be exploited.

Bangladesh should either amend The Citizenship Act, to allow refugees to become citizens of Bangladesh, or the Constitution of Bangladesh, to expand rights to all persons in Bangladesh and not only to citizens. This way, the Rohingya will be truly safe and have a place to call home.