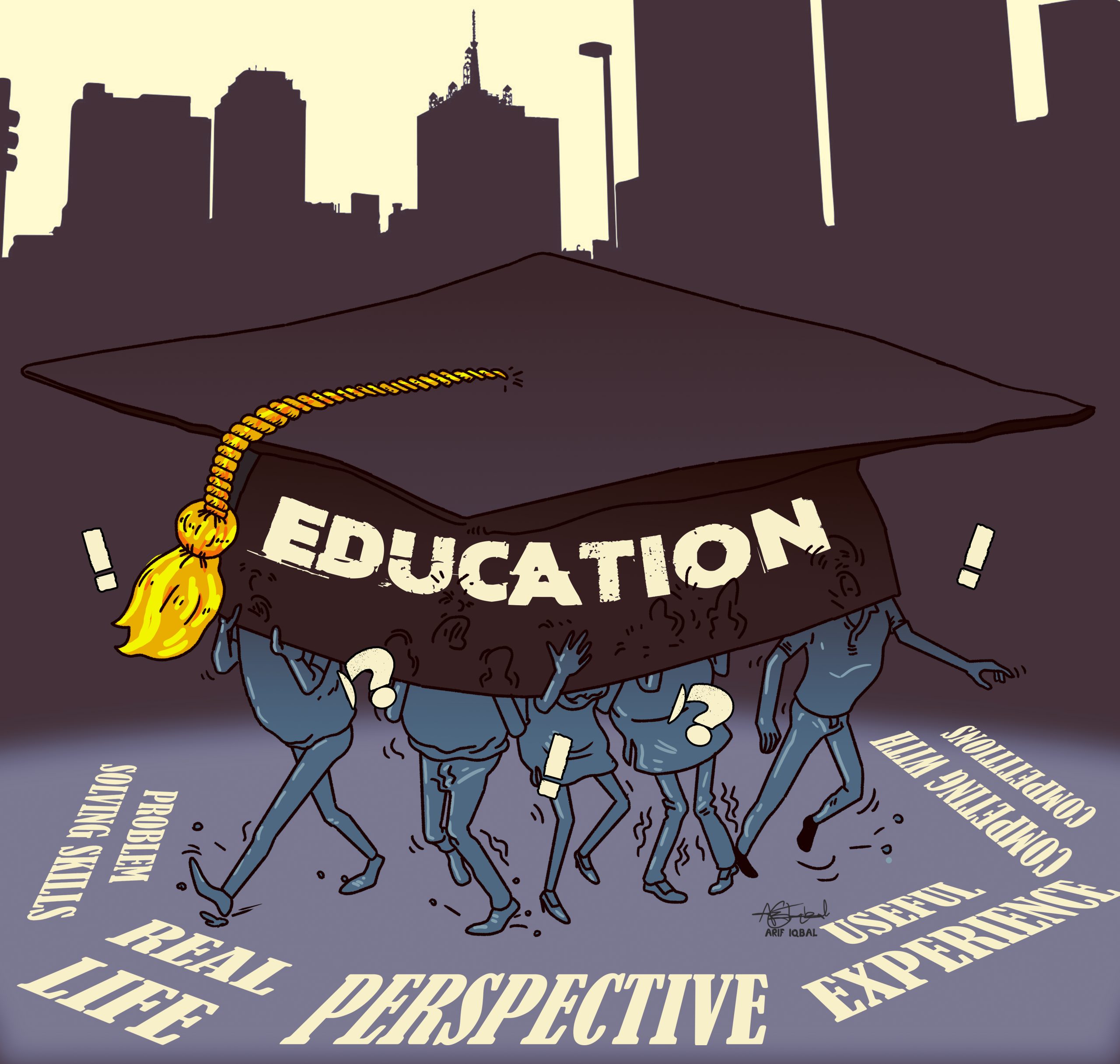

The Editor’s choice of name for this magazine dictates that my short essay ought to address an issue relating to progress. In this capitalist world, it is no surprise that progress is often measured in production. Those who argue that our country is making significant progress, use economic, production, and structural growth to substantiate their claims. But true progress cannot only be driven by the above-mentioned aspects. If that were the case, industrialization would have been the greatest achievement of mankind. In the progress of mankind, literature, philosophy, politics, and other important factors played equally or more important roles than mere increases in production. For instance, the enlightenment period played one of the most significant roles in the current “progress” of Western Europe. Our liberation, which is without a doubt the biggest contributor to our current progress was not pursued just to ensure economic growth. Rather, it was a result of significant political moments and the contribution of great thinkers of that time. To make “real progress”, society needs to replace the current order with a better or more advanced order. To find a better system, the members of society must identify what is wrong with the current system. For that, we need critical thinkers. In my humble opinion, our country is currently failing to produce critical thinkers. This essay argues that our current education system’s obsession with creating “skilled workers” by increasing dexterity is resulting in the creation of a generation of non-critical thinkers. I will take advantage of the nature of this publication and intentionally refrain from citing empirical studies. Instead, the claims made in this essay will be backed by first-hand observations.

Those who set the school curriculum do not treat school students as intelligent beings capable of forming their own opinion

Before entering the formal education system, children start learning at home. Unfortunately, our culture discourages dissent from the moment we learn to speak. The uncorrupted and curious minds of children are often candidly critical of the system they see around them. They ask questions, the answers of which would undress the ugly reality of this world and in turn make their parents uncomfortable. For instance, a child who is yet to be exposed to the unfortunate class system in our society may ask her parents why their household help eats in the kitchen while they dine at the dinner table. In most cases, parents do not wish to answer this question as they know the practice is immoral. In our culture (at least in most families), parents choose to silence their children instead of providing unpleasant answers. They are actively discouraged from saying anything “beyond their age”, without considering that thoughts beyond their age can be an early sign of brilliance. Our culture treats dissent as impolite. What their elders say is treated as axiomatic on the virtue of being uttered by someone older than them. Let us call this trend the “age factor” for the purpose of this essay. The above-mentioned system is hypocritical. Children are usually taught by their families that their religion is the one true religion. So, they are taught that at least five billion people in this world are living their life in the wrong manner. Just by believing in your religion, you are accepting that you know better than at least five billion people in this world. Many of them are, of course, older.

The culture of not challenging the practice of our elders is strongly and efficiently promoted in primary and secondary schools. At home, young minds are taught that those who are older than them are naturally wiser, and in school, it is implicitly taught that those who have more degrees are wiser. Let us call this the “degree factor.” Needless to say, the assumption of the degree factor is inherently flawed and does not need much explanation. From the very start of their school days, children are introduced to a sea of dogmas. Very few primary school teachers in our country have shown to possess critical minds, which is apparent from their lack of participation in academic discourse and method of teaching. The information children learn in primary school is presented as facts. From the get-go, children are taught to presuppose that whatever their teachers teach is true.

Additionally, since the government controls the curriculum, the party-in-power can control the dogmatic status of information. Those who set the school curriculum do not treat school students as intelligent beings capable of forming their own opinion. For instance, history is taught in school in a linear manner from a single perspective. Even the most benevolent regimes are guilty of altering history. Unless students are made aware of this trend in keeping accounts of history, they will never be able to appreciate the true nature of historical studies. A quick look at the Bangladesh and Global Studies (BGS) textbook for Class Eight may help to understand my argument. The BGS textbook does not start with a chapter explaining how to read and understand a book of this nature and what to do with the information obtained from such a book. Instead, the book directly dives into the history of colonisation. There is no reason to assume that a 12 to 14-year-old would not be able to appreciate critical information. Children of this age can process more complex concepts than the philosophy of history, such as poverty, death, discrimination, divorce, love, class, race, religion, and so on. To understand what it means to be a Bangladeshi, one must critically examine our complex history, not just the historical figures and unintelligent utterances of facts. Unfortunately, the current system does not facilitate such a learning structure.

Our current education system is obsessed with providing job-market-oriented education. The government knows that many students will quit school after completing their primary and secondary education. Thus, they focus on teaching students what they think would be “useful” in their professional life. Too often, we hear that education should be more “practical.” I see no problem with this claim. However, there exists a substantial problem with what is considered “practical” by many. Any keen observer of our education system would note that “theoretical” is considered the opposite of “practical.” Those who think that theory is not useful often confuse a theory with a hypothesis. A sound theory corresponds with practice and explains the practice most logically. A theory must have empirical evidence in support of it, otherwise, it would merely be a hypothesis. To gain a deep understanding of a practice, one must employ sound theories. For instance, if a law teacher only discusses legislation and case laws in her class, her teachings may become redundant if those legislation and case laws are repealed or overruled. If a teacher wants to provide holistic teaching of the subject she is teaching, she must discuss its underlying theories. Someone who knows how to cook one dish can only properly cook that dish. But a chef who understands how ingredients, heat, and spices work can cook many items and invent new ones. The creation of new knowledge may not be possible without a sound theoretical foundation. So, the “practical” approach to education may not be so practical if we avoid theoretical knowledge. Instead of undermining theoretical knowledge, the education system should focus on teaching how to properly handle theories. If our education system does not teach students to challenge established knowledge, innovation would decrease. To create something new, one must first identify the problems with the best existing knowledge.

Traditionally, students are supposed to exercise their minds most critically while studying at the university level. However, now most universities in our country are solely focused on creating industry-ready graduates. Universities take pride in the employability of their graduates instead of their social and political contributions. Those who hold this view have lost sight of the philosophy of academia. Educational institutions were not created with the sole purpose of increasing the dexterity of skilled workers. The very foundation of academia is challenging existing knowledge. Most students have subscribed to the idea of learning only those materials that they can apply in their jobs. This view has blurred the line distinguishing technical education from university education. If university education only focuses on satisfying the demands of the future employers of the graduates, it will not be able to produce graduates with original thoughts. While technical knowledge is important, the industry-oriented mindset will prove to be counterproductive in the long run. University students must learn to critically engage with the materials they are exposed to. The first step towards building a critical mindset is challenging their course instructors. Unfortunately, the bulk of our university teachers does not encourage constructive criticism. We cannot expect our graduates to challenge the current world order if they are not allowed to challenge their teachers.

There is a need for preparing students for the job industry. However, we must also focus on producing students capable of forming their unique opinions about society and politics. Skilled workers may create a rich country, but only socially, morally, and politically conscious citizens can bring about real progress. One would easily find countries with great wealth but without an iota of regard for human dignity, value, and rights. We must decide what kind of society we want to create for the future generation and design our academia accordingly.